I remember when we bought our first place in London and were incredibly excited when the survey arrived in the post.

After the drudgery of flat hunting for months, price negotiations (I mean agreeing to pay more than we ever imagined) and convincing a bank to give us a mortgage after one of us had just been made redundant, it was time for the tide to turn. This was the good bit, that little bit of process at the end, the proof that we had indeed been clever enough to choose the most perfect property on the market at the best possible price.

Wrong of course. Our survey for that little flat threw up so many issues it delayed the sale by 6 months and in the process we learned more than we had ever planned to about leaseholds, freeholds and English property law.

Hardened from multiple experiences like this we set out to get a survey on the cottage and braced ourselves for a laundry list of bad stuff – the surveyor did not disappoint!

There were a bunch of problems. The state of the septic tank could not be determined, the sewage plumbing in the cottage was not fit for purpose and plumbing in general needed some work. There was a water leak buried somewhere under the concrete in the bathroom causing damp in that area. There were structural problems with the chimney and they were recommending that it be replaced. Also a raft of other minor issues from joinery to window repairs.

We were expecting issues like that, but what we didn’t expect was such an extreme diagnosis on the damp related issues in the cottage. The surveyor carried out a number of rising damp tests. They do this by measuring the moisture in the walls at different heights above ground. Ours showed significant moisture – the walls were very wet inside.

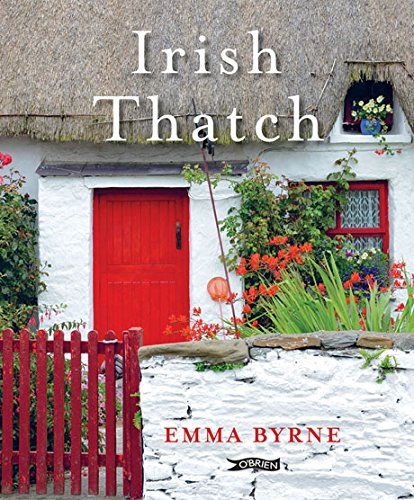

The reason was that the old stone walls had at some stage (perhaps in the past 50 years) been re-rendered with cement. Traditionally cottages had been finished with lime based materials which allow the absorption and evaporation of moisture more naturally. Cement, the cheaper alternative, locks in the moisture leading to rising damp.

The solution suggested was to completely re-render the whole cottage. This would involve a painstaking process of removing the cement and replacing it with lime based mortar, for all walls, both inside and outside the cottage.

This was giving us second thoughts on the purchase. We expected work, but early estimates had this adding another third or half to our budget. Thankfully our builder Tom was much more pragmatic. While he agreed that the preferred solution would be to re-render, he was willing to look at other options.

Tom suggested digging a french drain around the cottage to stop moisture entering the walls. Water had been draining off the thatch roof into the ground below, soaking back into the walls. A french drain would help divert the water away from the cottage.

We liked this plan and finally had the confidence to proceed with the purchase.